Neurovascular Structure and Function

Background : Cerebral Blood Flow and Angioarchitechture

Blood is a limited but vital resource for the brain. Normal neuronal activity and proper brain physiology are dependent on the neurovascular blood supply which provide the neurons and glia with oxygen, glucose, and waste removal. In addition to understanding its role in normal brain homeostasis, the study of cortical vasculature is important with regards to many neurological diseases with associated vascular pathology. In particular, stroke is currently the 4th leading cause of death in America, responsible for 130,000 deaths per year. Finally, a growing number of techniques utilize blood oxygenation measurements as a surrogate for measuring neuronal activity. This includes widely-used techniques such as intrinsic optical imaging (IOS) and blood-oxygenation level dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging (BOLD fMRI).

Yet despite the importance of the neuronal vasculature in both research and clinical contexts, the microvascular details of cortical blood flow have, until recently, remained largely unquantified. Notably, no large-scale quantitative maps of the complete neurovascular connectivity exist to provide insights into the dynamics of blood flow and blood perfusion within the brain.

Over the past decade, my colleagues and I have endeavored to elucidate some of the microscopic details of blood flow in the brain by undertaking research in two complementary directions: 1) In vivo imaging and perturbation of blood flow with micrometer resolution and accuracy, and 2) 3-D post-mortem quantitative reconstruction of cortical angioarchitecture to compute and predict patterns of blood flow across millimeter-scale regions of mouse cortex.

In Vivo Imaging and Manipulation of Cerebral

Blood Flow

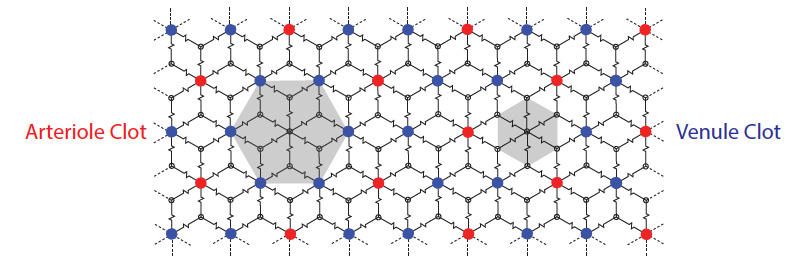

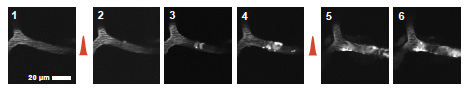

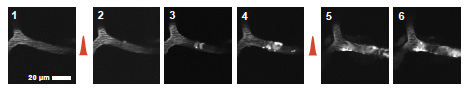

The flux of red blood cells (RBCs) in individual vessels in the rodent brain can be monitored in vivo using two photon laser scanning microscopy (TPLSM) through a cranial window. In addition, we have developed techniques that allow for optical manipulation of blood flow at the single-vessel level. These include the use of focused green light and a circulating photo-sensitizing agent in the blood to produce surface vessel occlusions as well the use of femtosecond pulse plasma-mediated laser ablation to damage individual subsurface microvessels. Experimental work with both Chris Schaffer and Nozomi Nishimura demonstrated that the flow in both the surface and subsurface cerebral vasculature are robust to single point occlusions. Flow reversals downstream of the occlusion allow flow to be restored just one junction (at the surface) or a few junctions (in the subsurface) downstream of the targeted vessel. This stands in contrast to the previously widely-held view that a single occlusion would generally lead to cessation of flow across an extended region of the downstream vascular network. In later work, Nozomi Nishimura showed that the penetrating arterioles which connect the surface and sub-surface networks are more susceptible to single-point occlusion, and thus serve as a "bottleneck" of cerebral blood flow.

The flux of red blood cells (RBCs) in individual vessels in the rodent brain can be monitored in vivo using two photon laser scanning microscopy (TPLSM) through a cranial window. In addition, we have developed techniques that allow for optical manipulation of blood flow at the single-vessel level. These include the use of focused green light and a circulating photo-sensitizing agent in the blood to produce surface vessel occlusions as well the use of femtosecond pulse plasma-mediated laser ablation to damage individual subsurface microvessels. Experimental work with both Chris Schaffer and Nozomi Nishimura demonstrated that the flow in both the surface and subsurface cerebral vasculature are robust to single point occlusions. Flow reversals downstream of the occlusion allow flow to be restored just one junction (at the surface) or a few junctions (in the subsurface) downstream of the targeted vessel. This stands in contrast to the previously widely-held view that a single occlusion would generally lead to cessation of flow across an extended region of the downstream vascular network. In later work, Nozomi Nishimura showed that the penetrating arterioles which connect the surface and sub-surface networks are more susceptible to single-point occlusion, and thus serve as a "bottleneck" of cerebral blood flow.

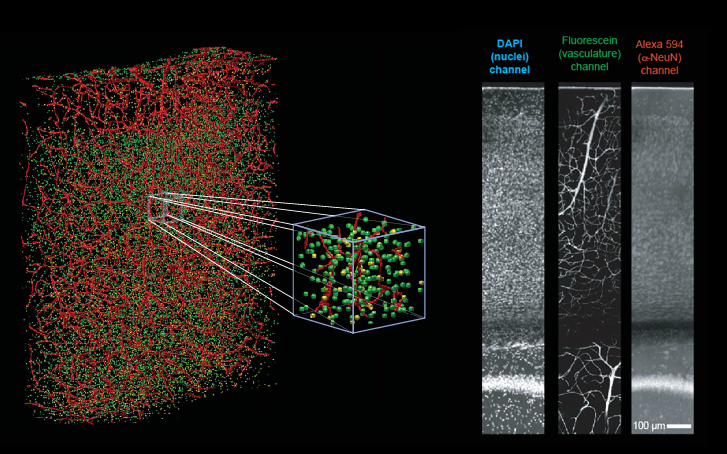

Futher intepretation of the flow data obtained from our in vivo imaging studies as well

data

from other methods that utilize blood flow and blood

oxygenation requires a detailed map of cerebral vascular

connectivity. To that end, we have used our

All-Optical Histology technique to perform in-situ

block-face imaging of vascular-labeled cortical

tissue. From these data, we are able to reconstruct

the full connectivity of the surface and sub-surface

vascular network across a volume that is 2 - 3 millimeters

on edge, and spans the depth of cortex.

Simultaneously, we label and record the position of every

neuronal and non-neuronal somata within the tissue

volume. This allows us to correlate the vascular

network to the surrounding neuronal tissue and any

organizational units within that tissue, such a the vibrissa

barrels in primary somatosensory cortex.

data

from other methods that utilize blood flow and blood

oxygenation requires a detailed map of cerebral vascular

connectivity. To that end, we have used our

All-Optical Histology technique to perform in-situ

block-face imaging of vascular-labeled cortical

tissue. From these data, we are able to reconstruct

the full connectivity of the surface and sub-surface

vascular network across a volume that is 2 - 3 millimeters

on edge, and spans the depth of cortex.

Simultaneously, we label and record the position of every

neuronal and non-neuronal somata within the tissue

volume. This allows us to correlate the vascular

network to the surrounding neuronal tissue and any

organizational units within that tissue, such a the vibrissa

barrels in primary somatosensory cortex. Using code developed specifically for this

purpose, we are able to extract a fully-connected vectorized

map of the cerebral vascular network within these

cubic-millimeter-scale tissue volumes. By carefully

measuring the radius of each vascular segment within the

network, and applying a previously-determined relationship

between vessel diameter and fluid resistance to blood of a

known hematocrit, we are able to produce deterministic

resistive model of the flow across the reconstructed

network. In silica experiments in which the

change in flow is measured after manipulation to a single

vessel resistance yield flow patterns that closely match

those found in previous in vivo experiments of the

same nature.

Using code developed specifically for this

purpose, we are able to extract a fully-connected vectorized

map of the cerebral vascular network within these

cubic-millimeter-scale tissue volumes. By carefully

measuring the radius of each vascular segment within the

network, and applying a previously-determined relationship

between vessel diameter and fluid resistance to blood of a

known hematocrit, we are able to produce deterministic

resistive model of the flow across the reconstructed

network. In silica experiments in which the

change in flow is measured after manipulation to a single

vessel resistance yield flow patterns that closely match

those found in previous in vivo experiments of the

same nature.From these reconstructions, we are able to conclude that, within the vibrissa barrel cortex, the microvascular angioarchitechture represents a fully-connected continuous network. This stands in contrast to the previously held-notion of (semi-) discrete neurovascular units. We find no evidence of such discrete units within the vascular architecture. Although we do find that flow sourced from a single penetrating arteriole is constrained to a finite lateral extent within the cortex, the "confined lateral flow" show no correlation to underlying cortical columns or "barrels". Furthermore, we are able to present a simple model of blood flow in the cortex that accounts for this lateral confinement of flow within the fully interconnected network. We find that the fluid resistance of the venules to be smaller than the effective net resistance of the microvascular network. Hence, the distribution of high pressure sources (penetrating arterioles) and low resistance sinks (arising venules) result in watershed domains that limit the extent of flow from any single source.